Anthony Comstock in Action

Publishers' Weekly 45:1155, March 17, 1894, p440.] --The Watch and Ward Society, of Boston, recently caused he arrest of B. Lewis, newsdealer, of 250 Hanover Street, on the charge of selling obscene literature. Lewis was indicted on seven counts, but the jury, after a long deliberation, could find him guilty on only two counts -- nammes, selling "The Arms of Love" and "Crimson Kisses." Lewis has appealed to the Superior Court. Count Zuboff, who was arrested on the charge of issuing obscene matter in putting forth his last book, "Violet," was acquitted on the 12 inst. Alexander McCauce, a South End Washington Street newsdealer has also been indicted on a charge similar to the foregoing for selling a Worthington edition of the "Decameron."

THE FAILURE OF THE WORTHINGTON COMPANY.

[Report in Publishers’ Weekly 45:1162, May 5, 1894, p684.] -- MR WORTHINGTON DISCHARGED. -- Richard Worthington was arraigned in the Tombs Court on Friday, April 27, on complaint of Joseph J. Little, receiver, who charged him with perjury. He furnished bail for examination on Tuesday, May 1. Justice Martin in the Tombs Court on that day discharged Mr. Worthington from custody.

PUBLISHERS’ WEEKLY MAY 5 STATEMENT OF LITTLE’S ACTIONS AND STATEMENT ON WORTHINGTONS FAILURE

Publishers’ Weekly 45:1162, May 5, 1894, p 681. --“Every man is a debtor to his profession, from the which, as men do of course seek to receive countenance and profit, so ought they of duty to endeavor themselves by way of amends to be a help therein.” – Lord Bacon.

THE ABUSE OF RECEIVERSHIPS.

THERE is an old proverb that the receiver is worse than the thief. This was not intended to apply to receivers in the modern sense, that is to say, the worthy gentlemen who as officers of the court, are put in charge and in absolute control of bankrupt estates, pending the settlement of accounts. But it is true that creditors are beginning to feel that the losses which are the direct result of bankruptcies are sometimes less than the losses which accrue under receivers' control of the estate of the bankrupt. THE WORTHINGTON FAILURE.

RECEIVER LITTLE has issued the following statement to creditors of the Worthington Company:

Office of the Receiver, “Very' truly yours", A long letter was received in reply, denying that he had made or authorized the false entries in the books. Personal interviews, in which it was stated that there had simply been careless book-keeping, and that the entries referred to had been made by book-keepers to correct their own faults, led to no satisfactory conclusions. The statement of the book-keeper, together with the report of an expert accountant regarding those particular entries, convinced me that they had been wilfully made, by direction of Mr. Worthington. In the meantime, however, the creditors held a meeting, and efforts were being made by Mr. Worthington looking to a settlement with them. In view of the deplorable business situation then existing throughout the country, and the fact that complicated litigations would need to be carried on -- for Mr. Worthington still maintained the integrity of the entries above referred to, and claimed, by the showing of these entries, to be a creditor of the company for $2555.62, his wife for $7336.00, and Miss E. Sproule for S1870.00, although, as before stated, none of them appear as creditors to the sworn list presented to the court. I looked with favor upon his efforts, believing that it would be to the advantage of the creditors to accept the cash offer he made. The facts of the particular case which I have selected for prosecution are as follows, viz. I have endeavored to conduct the affairs of this receivership as carefully and as economically as if it was my own business, and hope within the next thirty days to receive the proceeds of the sale just finished, when I shall ask the court for permission to pay it out to you In dividends, my chief regret being that it will be but a very moderate one, probably about twenty-five or thirty per cent., with hopes that later there may be a very small additional dividend derived from the sale of the recovered books above referred to, some slight legal formalities being necessary before I can sell them, and from endowment life insurance policies on Mr. Worthington, the premiums of which were paid for by the money of the Worthington Company, and which I hope to obtain by order of the court. **********

[Publishers' Weekly 45:1160, April 21, 1894, p609.] --The Receiver's sale of the Worthington plates, books, and stock has been very well attended, the crowds and general interest reminding us of the old trade sale days. Satisfactory prices have been obtained, and the spirit of the sale has been exhilarating and exciting.

[Publishers' Weekly 45:1160, April 28, 1894, p647.] --The Receiver's sale of the Worthington plates, books, and stock will cause many perennially popular books to find themselves in the lists of new publishers. In the next week's issue we shall give a full statement of where the bookseller shall now direct his orders for books formerly published by Worthington Co. As there are upwards of 400 book in the Worthington sale, it has been impossible to get them properly listed and their various buyers verified for this number. We intend to make an alphabetical list of the books sold, which the bookseller may keep on hand for ready reference.

[The Publishers' Weekly No. 1162 May 5, 1894, p684-687.] The ASSIGNEE'S SALE OF THE WORTHINGTON PLATES. is a full record of the sale, with name of buyer and price paid for each lot.

[The American Newsman II:5 (May 1894), p8]. --At the Worthington sale held in New York recently, the book publishers from here who went and bought largely were Donohue, Henneberry & Co., E. A. Weeks & Co., Rand, McNally & Co. This will bring to the West many good sets of plates and books that ought to sell rapidly. Chicago correspondent.

[The American Newsman II:5 (May 1894), p14]. --At the Worthington sale J. J. Little, receiver of the Worthington Co., submitted to Mr. Anthony Comstock some book which he was told Mr. Comstock had restrained Mr. Worthington from selling some ten years back, and submitted to the court the question whether he had any right to sell as assets of the company books that had been put under Mr. Comstock's ban. In looking over these forbidden books, Mr. Comstock for the first time glanced into the pages of "Tom Jones," and is shocked to think that this book has been sold for one hundred and forty-five years. In future he will do his best to check its sale. Gibbon, Thackeray, and Coleridge held different opinions about "Tom Jones," hut they are only immortal critics and -- had read the book.

[The American Newsman II:6 (June 1894), p14]. --WILLIAM MORRISON-BOOKSELLER. -- Mr. Morrison has a book shop in Brooklyn. He insists on calling it a book shop, after the English style. He is always interesting and instructive. New York Tribune June 29, p5.] --RICHARD WORTHINGTON ARRESTED. The Receiver of the Worthington Company Accuses Him of Misappropriating Its Funds. *******

[Publishers’ Weekly #1170 June 30, 1894, p942-43]. --ANTHONY COMSTOCK OVERRULED. --JUSTICE [Morgan J.] O'BRIEN, [1852-1937] of the [New York State] Supreme Court, to whom Mr. J. J. Little as receiver for the Worthington Co. made application for instructions concerning the final disposition of certain books which were found among the assets of the company, and which are now in his custody, and respecting which it is alleged by Anthony Comstock of the Society for the Suppression of Vice, that they are unfit for circulation, that they come under the designation of immoral literature, and as such should be excluded from sale, handed down the following decision: **********

[Publishers’ Weekly 45:1170, June 30, 1894, p944].IN RE THE WORTHINGTON CO. --J. J. Little, receiver for the Worthington Company, has succeeded in recovering the 62 cases of books stored by Mr. Worthington, first in Chicago, and subsequently in the Tower Storage Warehouse in New York, and 26 cases in the Fifth Avenue Storage Warehouse, also in New York, both consignments in the name of Margaret Worthington. These books, together with those released through the decision of Judge O'Brien, of which we make note elsewhere in this issue, and some other property recovered, especially the Bulkley, Dunton & Co.'s claim, which has been decided in Mr. Little’s favor by Referee Sandford, represent a value of upwards of $12,000, the proceeds from which will accrue to the profit of the creditors of the defunct concern. Mr. Little intends in a few days to ask the court for permission to pay a dividend of 33 ½% to the creditors. *********

[The American Newsman II: 8 (August 1894), p8.] --ANTHONY, OH! ANTHONY! --Mr. Comstock, who has risen superior to the Supreme Court, announces in ungrammatical and incoherent language that he will prosecute everybody in America who attempts to sell the classics endorsed by Judge O'Brien, of the Supreme Court. Comstock will probably have an opportunity to put his threat into execution, as the advertising pages of the papers show that many of the booksellers who were frightened by him into such a position that they were afraid to offer these famous books to the public have taken heart, in view of the decision of the Court, and will now get rid of the stock which they bought in good faith, and without any notion of the terrible wickedness which Mr. Comstock believes it to contain. The terror which Comstock inspired among publishers is almost ludicrous. It is perfectly well known that he has no legal reason for the control which he exercises over the publishing world, but for some reason, the publishers continue to be in abject fear of him at all times. [American Newsman 1894-08 p12].A WISE DECISION.. Judge O’Brien, of the Supreme Court of New York, handed down a decision recently to the effect that Fielding’s “Tom Jones” and several books of like character, are not immoral and obscene, Application was made by the receiver of the Worthington Company for a court ruling on the subject as a guide to the final disposition of the books. The decision of course permits the books to be sold without the receiver rendering himself liable to criminal prosecution. The very sensible remarks of the judge upon the point at issue deserve to be widely printed. They are as follws: “It very difficult to see upon what theory these world-renowned classics can be regarded as specimens of that pornographic literature which it is the office of the Society for the Suppression of Vice to suppress; or that they can come under any stronger condemnation than that high standard literature which consists or the works of Shakespeare, of Chaucer, of Laurence Sterne, and of other great English writers, without making references to many parts of the Old Testament scriptures, which are to be found in almost every household in the land. The very artistic character, the high qualities of style, the absence of those glaring and crude pictures, scenes, and descriptions which affect the common and vulgar mind, make a place for books of the character in question entirely apart from such gross and obscene writings as it is the duty of the public authorities to suppress.” Before rendering his decision Judge O’Brien consulted his associates on the bench, so the question may be considered finally settled.

*********

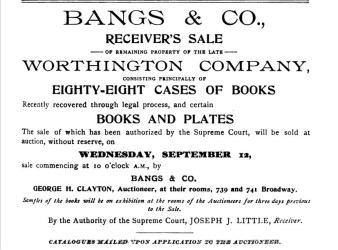

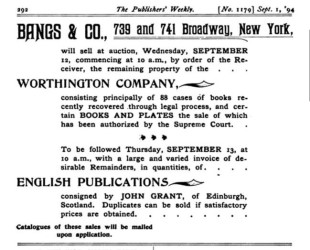

[Publishers’ Weekly 46:1179, September 1, 1894, p271. Bangs & Co., as already noted, will dispose of the remainder of the stock of the defunct Worthington Company on the 12th inst. This remainder consists principally of 88 cases of books recently recovered through legal process, and certain books and plates the sale of which has been authorized by the Supreme Court. On the day following this sale they will dispose of a large and varied invoice of desirable remainders in quantities of English publications, consigned by John Grant, of Edinburgh, Scotland.

[Publishers’ Weekly 46:1180, September 8, 1894, p306]. New York City. -–Joseph J. Little, receiver for the Worthington Company, has been authorized by the court to pay a dividend of 30 per cent. On all claims that have been properly proven against that corporation. Checks are ready now.

[Publishers’ Weekly 46:1181, September 15, 1894, p327]. --SALE OF PLATES OF THE WORTHINGTON COMPANY. THE electrotype plates of the following books belonging to the late Worthington Company were sold on the 12th inst., at the prices and to the parties mentioned below. The Mr. "Clark" who bought the plates of Payne's translations of the "Arabian Nights," "Aladdin," and "Tales from the Arabic," it was understood acted as intermediary, but for whom, could not be learned at the time of our going to press:

< "Arabian Nights." The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night, done into English prose and verse, from the original Arabic, by John Payne. 9 vols., 3351 pp. London, 1884. $76 per volume. Clark. [American Newsman 1894-11 p23]. W. E. C. Harrison & Sons, the old time booksellers, are doing a very fair business in holiday goods. Their store is packed from floor to ceiling with juvenile toy books and other publications that will meet the demands of the Christmas shopper. The senior Mr. Harrison attended the Worthington sale in New York, buying a thousand dollars worth of books at an extremely low price. The customers of this house will find it advantageous to seize this opportunity for bargains in holiday books. Mr. Harrison pater is just across the line of sixty-three but is as young and vigorous as ever. He tells every one that he is letting the young men attend the business now, but outside of a summer vacation or something of that sort, you will always find brother Harrison at his post from nine o’clock in the morning until the store closes. Stanley Harrison, his son, is the business head of the house.

*********

[The [New York] World Evening Edition, Monday, October 8, 1894, page 1; also published in the “Sporting Extra” edition, abbreviated, page 5.].

RICHARD WORTHINGTON DEAD. Richard Worthington, secretary-treasurer and general manager of the bankrupt Worthington Publishing Company, died suddenly at 10:30 o’clock last night at his summer home at Sea Clif, L. I. His age was fifty-eight years.

Rumors were current to-day, owing to the suddenness of his death that Mr. Worthington had died under mysterious circumstances. Of late he had been oppressed by business troubles, aggravated by his arrest for alleged misappropriation of the funds of the company.

Lawyer James M. Fisk, of 206 Broadway, attorney for Receiver J. J. Little, who has charge of the assets of the bankrupt concern, told a reporter for "The Evening World" this morning that Mr. Worthington had been complaining for some of diabetes.

Later word came from Sea Cliff that apoplexy was the direct cause of his demise.

The deceased leaves a widow, but no children. A brother and several nephews and nieces were his only relatives.

In years gone by Worthington was a well-known figure in the book-publishing business. He failed back in 1885, but managed to get into business again, and organized the Worthington Publishing Company. They failed in January, 1893. A receiver as appointed, who last June caused Mr. Worthington’s arrest. He was locked up in Ludlow Street Jail, but finally furnished bonds of $5,000 for his appearance and was released.

Lawyer Fisk said that when the affairs of the Worthington Company were investigated by Receiver Little it was discovered that there was a shortage of $70,000.

Lawyer Fisk began suits in the Supreme Court against Worthington and his wife and Elizabeth Sproule, a sister-in-law, to recover the amount alleged to have been appropriated from the Publishing Company’s funds by Worthington, and said to have been transferred to his wife and Mrs. Sproule.

Worthington had set up a counter claim against the Company for alleged profits and salary amounting to nearly enough to cover the shortage.

When Referee William H. Willis inquired into the case he reported that Worthington had no valid claim.

The accounts are said to show that Worthington paid all his household expenses, the rent of a flat in this city, pew rents and many other bills out of the funds of the company.

He had taken out three policies of life insurance in the Mutual Life Insurance Company, to being for $10,000 each and one for $2,000, and also three policies in the Aetna Life Insurance Company, of Hartford, for $5,000 each. The premiums on these policies, it is claimed by Mr. Fisk were paid out of the funds of the Publishing Company, and therefore are a part of the assets thereof, which are being sued for.

Mr. Fisk said the suits would be continued against Mrs. Worthington and Mrs. Sproule.

*********

New York Tribune, October 9, 1894, p5. Obituary. RICHARD WORTHNGTON.. --Richard Worthington, the publisher, died suddenly at 11 o’clock Sunday night at his summer home, at Sea Cliff, Long island. He had gone to church in the evening, apparently in good health and spirits, but later was taken with a fit of suffocation, and before help could be summoned he died. For several years he had been threatened with diabetes.

Mr. Worthington was born in Lancashire, England, about sixty years ago, and, it is said, was the oldest publisher in the city, though not course the oldest house. He began business first in Montreal where he settled on his arrival from England about thirty-five years ago. From Montreal he moved to Boston, and from Boston twenty-five years ago he came here. In New York his business was carried on successfully at No770 Broadway, No. 28 Lafayette Place, and last at No. 747 Broadway. Originally it was under the style of R. W. Worthington & Co., which was changed in 1885 to the Worthington Publishing Company, Incorporated. With a comparatively small capital stock, Mr. Worthington was a publisher of wide ambitions. Last year the company applied for a voluntary dissolution, and Joseph J. Little, of J. J. Little & Co., publishers, Astor-Place, was appointed receiver.

Among the noteworthy books issued by Mr. Worthington was an edition in thirteen volumes of Payne’s translation of the “Arabian Nights,” a reprint from the original London edition. The translation of Payne, the famous Oriental student, ranks with that of Burton as one of the scholarly renderings of the Eastern tales, but Anthony Comstock prevented the sale of the Worthington Company’s edition as coming under the head of improper publications. The edition, an extremely valuable one, was, however, finally in the market again as the result of a recent memorable decision by Justice O”Brien, of the Supreme Court.

Mr. Worthington leaves a widow in this country and a brother in England.

*********

[New York Tribune, October 10, p10. LONG ISLAND. Sea Cliff. –-Although it is generally believed that Richard Worthington the publisher, who died suddenly as was supposed from apoplexy on Sunday night, did not commit suicide, but died a natural death , coroner Duryea has decided to hold an inquest in the case next Monday. There was considerable talk about the village that Mr. Worthington had committed suicide owning to financial problems, and the persons who circulated the report said that the sudden embalming of Mr. Worthington’s body was to hide the signs of suicide in order that the Coroner could not tell whether the death was natural or not. The undertaken, Cornelius, who embalmed the body denies that he did so hurriedly, and said he had the permission of the Coroner. The funeral will take place this evening at the Sea Cliff Methodist Church.

*********

[Publishers’ Weekly 46:1185, October 13, 1894, p584.] OBITUARY NOTES. --RICHARD WORTHINGTON died suddenly before midnight of Sunday, the 7th inst., at his home in Sea Cliff, L. I. He had for some time been treated for diabetes, which, aggravated by the worry of the past six months, no doubt hastened his death. He appeared to be in good health on Sunday, and attended church in the evening. He retired about eleven o'clock, but got up again, complaining of a suffocating sensation. His wife and Miss Sproule were present, and the latter went for Dr. Zabriskie, of Glen Cove but on their return found that Mr. Worthington was dead.

Mr. Worthington was born in Preston, Lancashire, England. His father was a merchant of comfortable means, and gave his son a good education. When eighteen years old young Worthington entered the grain business, and after pursuing this occupation for eight years emigrated to Canada and settled in Montreal, where for a time he continued the grain and subsequently a commission business, without much profit, however. Encouraged by a friend, he bought a book and stationery store in Montreal in 1861. His first venture in publishing occurred about this time, and was a "History of the Province of Canada." which had a wide circulation. Mr. Worthington, however, devoted the most of his attention to the stationery trade, which in a few years grew to considerable proportions. Encouraged by his success he established a branch in Boston in 1867, which in time absorbed all his attention and he gave up his Montreal business. In Boston the character of his business changed altogether, and henceforth he made the sale of standard English books his specialty. In 1874 be opened a branch house at 750 Broadway, to which he removed altogether in I876, after having failed in Boston. At this time Mr. Worthington had one of the largest and most carefully selected stocks of rare English books that could be found in New York City.

From January, 1885 (in which year he formed the R. Worthington Co., and since which he occupied successively the stores at 770 Broadway, 28 Lafayette Place, and 747 Broadway), to January, 1893, Mr. Worthington's business career was marked, and finally closed in a failure, the details of which are still fresh in the mind of the trade. Mr. Worthington was always more of a bookseller than a publisher, and preferred to purchase an entire edition of a new English publication rather than to assume the copyright of it on his own account. He was the importer of the English edition of “Chambers' Encyclopedia" and he also introduced other standard works of reference. He was a man of vast schemes, which, owing to lack of capital and loose calculations, invariably ended in shipwreck

*********

[Publishers’ Weekly 46:1193, December 8, 1894, p1015].

END OF THE WORTHINGTON LITIGATION. On the 1st inst. Justice Truax of the Supreme Court signed an order authorizing the receiver of the company, Joseph J. Little, to collect all the outstanding insurance on the life of the late Richard Worthington and to pay to the widow, Margaret Worthington, 37 ½% per cent. of all moneys so collected. In consideration of this the receiver of the company is to discontinue all suits and discharge all judgments now outstanding against Richard Worthington, Margaret Worthington, and Elizabeth Sproule. Margaret Worthington, on her part, is also to discontinue all contested actions and adjust and compromise conflicting claims.

The petition of the receiver sets forth that, on his appointment, he discovered that Richard Worthington, who was at one time secretary, treasurer, and general manager of the company, had in force policies of insurance on his life, in the Mutual Life, Mutual Reserve Fund Life, the Aetna Life, and the Union Central Life Insurance Companies, aggregating $40,000. He discovered that the larger part of the premiums on these policies had been paid out of the funds of the Worthington Company, and at once took steps to have these policies, which were made payable to the widow, made a part of the company's assets for the benefit of all the creditors.

The receiver further states that Richard and Margaret Worthington and Elizabeth Sproule had also appropriated funds of the defunct company. On October 7 last, Worthington died, and actions brought by the widow and Elizabeth Sproule against the receiver were dismissed, and the latter received judgments for $910.25 against Mrs. Worthington and for $149.05 against Elizabeth Sproule. Under the order these two judgments are to be cancelled. The receiver is also empowered to bring suits against any insurance companies, if it is found necessary.

The creditors of Worthington Company are fortunate in having a business man to wind up its affairs. It is seldom that any important dividends are paid out of the assets of a corporation where there are so many complications as there were in this instance.

The receiver has already paid one dividend of thirty per cent., and hopes that he may pay another substantial dividend from the results of this compromise with Mrs. Worthington.

*********

Last revised: 4 February 2024

The case of the United States Book Company is fairly in point. When this company and the satellite concerns in its orbit were forced to confess bankruptcy, the court appointed as receiver one of the most esteemed business lawyers in New York, who had bad large experience in the handling of bankrupt estates. A clearheaded business man of this sort was needed to unravel the tangle and hold the property under protection of the court until such time as the assets could be figured and some arrangement made for a division among the creditors of what was left. This has proved to involve the practical continuation of the business at the expense of the creditors. The receiver was not a man acquainted with the book trade and he could only rely upon such agents as he found to carry on the business. A large and complicated business is not likely to be continued in this way without continuing losses, notwithstanding the honest and accurate handling of accounts which may be expected from a receiver like Mr. Gould. As a result, the assets of a concern are likely to diminish steadily until, in despair, the creditors who have real interests at stake are only too willing to let what remains of the good-will, or the ill-will, go back into the hands of those who were originally responsible for the wrecking of the business. In the present case, we cannot learn that the creditors' committee of five, Messrs. John I. Waterbury, Manhattan Trust Co., chairman; Schuyler Quackenbush, banker, 38 Broad Street; F. W. Hopkins, broker, i2 Broadway; Austin W. Fletcher, lawyer, 29 Broadway, and D. G. Garabrant, of Buckley, Dunton & Co., 75 Duane Street, none of whom are practical publishers or booksellers, have done anything effective, and the results of drift, In the publishing business, in hard times, are not likely to be altogether satisfactory to creditors.

We take this as an example of what is a present and pressing evil in the business world. A receiver, as an officer of the court, cannot settle previous debts, and in one sense stands in the way of an early settlement. He is there to see that no more losses occur, but, nevertheless, this very process sometimes invites new losses. It is difficult to see quite the best way out in such cases, and we have done our present duty in calling this matter to the attention of those concerned. One useful reform might be a quarterly report of a receiver to the court, which the receiver would also send to the creditors.

THE receiver of the Worthington Co., Hon. J. J. Little, has taken some such course -- and it is “greatly to his credit” to have done it so boldly. It is evident that the path of the receiver who undertakes to do positive instead of negative work is not always a happy one. We print elsewhere the letter addressed by him to the creditors of the Worthington concern, the most trenchant contribution yet made to the literature of trade bankruptcy. Mr. Little is certainly entitled to hearty thanks for hard work and fearless rigor, whether his charges are tight or wrong, and his endeavors to clear the air of the book trade should be appreciated.

THE failure of the "Elzevir Co.," of which Mr. John B. Alden is a leading spirit, is recorded this week. A valuable chapter of trade history could be written of the bankruptcies of the successive and protean enterprises with which Mr. Worthington, Mr. Alden, and Mr. Lovell have been associated.

(p>

747 Broadway, New York, May 1, 1894.

To the Creditors of the Worthington Company.

GENTLEMEN: Although there is no law directing the receiver of a corporation to make a report to its creditors, yet, there being no law, so far as I know, against such action, and so long a time having elapsed since my appointment, it appears to me that a statement explaining why it has not been possible to pay a dividend sooner would be acceptable, I therefore address you.

Had I known at the beginning what days and nights of labor were in store and what unpleasant duties were to be forced upon me, I could not have been induced to accept the position. Having accepted it, however, and realizing that I was the personal representative, not only of every creditor of the corporation, but of the Supreme Court itself, I have not failed to do my full duty as it has appeared to me, in spite of threats or of pleadings.

I was appointed temporary receiver on January 26, 1893. Mr. Richard Worthington, who, from the organization of the company, had been its business manager, and was its secretary and treasurer, and in whose integrity I had confidence, even if I may have questioned his business judgment, was of course and almost of necessity kept as one of the chief advisers. The schedules of assets and liabilities filed with the court at the time of asking for a receiver had been made up under his personal direction and supervision, and was sworn to by each of the trustees (himself, Mr. Doman, who was a nephew of his wife, and a Miss Sproule, of whom you will hear again). No member of his household was included in these sworn lists as a creditor.

After awhile rumors reached me to the effect that property of the company had been taken to a distant State, shortly before the appointment of the receiver, and not properly accounted for. I demanded of Mr. Worthington a full explanation, if any such thing had been done. His answer was a most positive denial. Perhaps no better explanation can be made of what was said regarding these shipments of books out of the State than by inserting here a letter, written at the time, concerning his statement.

“New York, April 27th, 1893.

“Dear Sir: After our conversation of yesterday afternoon, during which you stated that certain books had been sold to R. Worthington & Co. and shipped to Chicago, months before my appointment as receiver: that the transaction appeared regularly upon the books of the company: that the: goods had been paid for by notes: that the East River Bank had discounted these notes; that the Company had received the proceeds of said discounted notes; that these notes had subsequently been paid by Mrs. Worthington; and that everything regarding the transaction was perfectly regular and in order; I looked over the books to verify these statements, that I might be prepared to answer inquiries at the court proceedings on Monday next, and was greatly shocked to find that apparently the statement made by you was not correct, but rather that within a few days past you have had numerous entries made in the hook, which entries are fictitious, the purpose of them being to bear out as correct the statements above narrated.

"If this apparent mutilation of the books be verified, it is a very important matter. Not only is it a gross abuse of my confidence and an unpardonable discourtesy, but is no doubt a very serious contempt of court. Moreover, it would appear to be a concealment of the assets of the Worthington company.

"I hope you may be able to satisfactorily explain the apparent contradiction of the books to your statement, as otherwise you and I cannot longer continue our present relations, and it will be for the court and the creditors to say which shall retire.

"l shall be very glad to receive, at the earliest moment possible, any statement you desire to make regarding the matter, and request that it be in writing, that no misapprehension may hereafter arise as to what is said.

"Do not send by mail, but band your communication, sealed, to Mr. Metcalf, who will at once forward to me, should I be away from the store.

JOSEPH J. LITTLE, Receiver."

Miss Sproule has lived in Mr. Worthington’s family ever since she came to the United States. Testimony was given before Referee Willis in the case of Mrs. Worthington’s claim, just finished, that she was the housekeeper; also that for about one year she bad served in the store in a minor position, for which she was paid eight dollars per week. Mr. Worthington himself swore that she was not related to himself or his wife, although in the proceedings before Referee Odell, in the spring of 1893, he swore she was his sister-in-law; and several years ago, while under examination in supplementary proceedings, he swore that she was a cousin either of himself or his wife. In the present proceeding she was made to appear by the minutes of the secretary (Mr. Worthington) as the president of the Worthington Company, although it could not be shown that she had ever performed any official act as president, while we did show that Mrs. Worthington had signed hundreds of checks as president during the particular time that Miss Sproule claimed to hold that office. She also appeared as a capitalist, it being asserted that she loaned tens of thousands of dollars in a single transaction.

You will readily understand that if I undertake to inform you in detail why all those things were attempted to be shown, a large book would be necessary, as there were several volumes of testimony taken regarding those monstrous claims of the Worthington household; you will be content for me simply to say it was deemed necessary, if they were to substantiate the claims they had presented.

To increase the perplexity and difficulty surrounding the investigation, Mr. Worthington claimed the right to act in several capacities at the same time. As the business manager of the Company, he would assume to sell property to himself as the agent of his wife and Miss Sproule, whether with or without their personal knowledge or presence.

The efforts of Mr. Worthington to compromise with the creditors were not successful, and on the 13th of October the court appointed me as the permanent receiver of the company, ordering the dissolution of the corporation, the assets to be disposed of and the proceeds distributed among the creditors.

Shortly thereafter Mr. Worthington presented to me sworn claims on behalf of his wife and Miss Sproule, aggregating more than $71,000 as well as laying claim to the larger portion of the book stock, electrotype plates, office furniture, etc., remaining on hand, and in my possession as receiver.

You may imagine the task then before me when I state that the claims were made upon the theory that, after the failure of Mr. Worthington in 1885, his wife bad advanced him more than $40,000 to pay his creditors, and for this be had given her bills of sale of all property turned back to him by Mr. Jenkins, the assignee, upon the completion of the compromise with his creditors after that assignment. That all of this property had been left by her for sale and use by the Worthington Company, and must be accounted for. Upon my application the court, on the 8th of December, appointed a referee, William H. Willis, Esq., of 115 Broadway, to bear and determine the validity of those claims, I having rejected them all, and for four months he has been taking evidence regarding the same, and has just rendered his report to the court, finding that all the claims presented were fictitious.

Mr. Worthington produced bills of sale(?) to Mrs. Worthington, and maintained that unless the receiver could show title, all the property still belonged to her. It was no easy task for a receiver to produce invoices of many years ago, when the interests of those who had been the custodians required that they should not come to light. However, important invoices were discovered and annual inventories were critically examined, with favorable results; papers offered as evidence of title against the company were proved to be simply manufactured at a recent period; and finally, the case was so thoroughly exposed that it broke down, even before we had placed our expert accountant on the stand, on the 14th of April, the attorney for the Worthingtons stating to the court his surprise at the situation, and withdrawing from the case, thus abandoning all the claims presented.

Mrs. Worthington was unable to explain where she got the large sums of money which it was claimed she loaned to her husband and the company. The only money of her own that she could account for. previous to the failure of 1885, was one thousand dollars, which she had in the Bleecker Street Savings Bank, notwithstanding she was named as a preferred creditor for a large amount at the time of the failure in 1885.

We are able to show that, previous to the failure of 1885, very large quantities of books were sent out of the State, but sold after the assignment, the proceeds being turned over to Miss Sproule instead of to the assignee, and thus her apparent wealth was accounted for.

Much false evidence bad been given, documents had been made in secret and sworn to as true before the court, even the secretary's book of minutes being bunglingly altered in attempts to make them uphold these false claims. All this had involved the estate in thousands of dollars of expense, thereby reducing the dividends to the creditors to that extent. Under these circumstances I deemed it my duty to select at least one case from the many, and prefer a charge of perjury against Mr. Worthington, as otherwise I had expended your money simply to prevent his taking what property be had not already taken as an officer of the company while managing It. The report of the expert accountants show that that the Worthington household, consisting of Mr. and Mrs. Worthington and Miss Sproule, are justly indented to the estate for more than sixty thousand dollars, instead of it being indebted to them for more than seventy-one thousand dollars. Suits have already been commenced against them for the amounts so shown to be due. I have also secured warehouse receipts for eighty-eight cases of books which were stored in Mr. Worthington’s name, a portion of them being the books shipped to Chicago; and let me here note that twenty-eight cases of these books were shipped to Chicago as early as October, 1892, charged to no one, and no entry whatever made in the books, the carman's receipt who took them to the railroad being the only record found.

In order to prove title to the books improperly shipped to Chicago, Mr. Worthington testified that they had been sold to his wife, who, he claimed. was doing business under the firm-name of R. Worthington & Co.; that she had paid for the books by giving notes: that the notes had been paid over to Miss Sproule, as the company owed her money: that at their maturity Mrs. Worthington had taken up or paid the notes; he went so far as to produce three notes which he identified as the notes so given; he also produced three checks, drawn on the East River National Bank, of the same amount as the notes, and bearing dates corresponding to the dates when these three notes matured, and testified that these particular checks were paid for these particular notes; whereas the whole statement appeared to be false, the cashier of the bank testifying that the bank had never received the identified checks in payment of the identified notes, and, if possible, worse than all, he testified that at the times the checks bear date Margaret Worthington, whose name was signed to those checks, had no account to the bank from which said checks could or would have been paid had such been presented.

I realize the importance of such a serious charge, but am fully persuaded that I should have failed in my duty to you and to myself bad I pursued any other course. This slight outline, which might be continued almost indefinitely, will help you to a correct judgment of the situation, and thus enable you to approve or otherwise what I have very reluctantly determined was my duty in the premises.

A judicial examination of the perjury charge was concluded at the Tombs Police Court today, the judge deciding not to hold Mr. Worthington for the action of the Grand Jury.

Had not these claims of the Worthington household been successfully resisted, I am of the opinion that the creditors of the corporation would have received but a very trifling dividend, if any at all.

In case any one may think that action looking to criminal prosecution should have been taken at an earlier date, I beg to say that what requires but a few minutes to read and understand, when placed in form of this statement, was slowly developed by months of hard investigation, some of the most important links in the chain of evidence having but recently been brought to light. Early In the autumn of last year I deemed it my duty to entirely dispense with the services of Mr. Worthington, and acted accordingly.

Very tru1y yours,

JOSEPH J. LITTLE, Receiver.

”A little better than last month. After all it is getting’ about like this: what the dry goods stores can't or don t get, we retail booksellers get. I am now getting ready for the Summer trade and I have sent to all my customers and the people who live in this district, a small catalogue marking out all books suitable for Summer reading. This method pays me and I have done so for the last five years.

"Anything new?," I asked. "Have you read Receiver Little's document on Worthington? it is a 'corker.' It is about time somebody showed this man up. Little does not mince his language: very politely he calls Worthington a perjurer and thief! This old rascal has been working the crooked business for a long while, but at last he was cornered. I heard all about those books shipped to the Masonic Temple, Chicago, a year ago. Worthington was then getting ready to fail. It seems he would have come out all right on this last deal too, if some of the creditors who held his notes of a former failure that were never paid, did not obstruct the settlement. It is about the fourth failure of Worthington. It is his last. Little's exposure has killed him deader than a door nail. I see his old pal Alden has also made his annual failure. Think of it, he has failed for $45,000. Would anybody believe when Alden failed about two years ago, that he could again receive credit for $45,000. Such men as Alden and Worthington are making it possible for Socialism to grow and flourish. A system is wrong that will allow such vultures to wax and grow fat off the misery of others. One thing I notice the liabilities of Alden are growing less with each successive year. I expect to see him fail in the near future for about 15 cents. He has got into the habit now, and he cannot stop it, if even he would.

Business will be better for the retail bookseller before the year ends. Prices, wholesale and retail, must take a rise. I don't have one book drummer call on me now for five I had four months ago. This is a clear indication to me."

Richard Worthington, formerly a publisher at No.747 Broadway, was arrested by a deputy sheriff yesterday on the charge of misappropriating $19,065.71 of the funds of the Worthington Company. He could not give the bail of $5,000 required by Judge Brrett, and was locked up in the Ludlow Street Jail.

The accusation was made by James M. Fisk, a lawyer, at No. 206 Broadway, who is counsel for the receiver of the Worthington Company, Joseph J. Little. The concern, of which Worthington was the controlling spirit, was incorporated on June 15, 1885, and became bankrupt on January 26, 1893. Mr. Little’s examinations of the books convinced him that Worthington had wrongfully taken large sums of money from the corporation.

Worthington has been in business here for a long time. He failed in the seventies, paying only five cents on the dollar. In 1885 he became bankrupt again. This time his creditors received 25 cents on the dollar. Then he got up a corporation, of which he was secretary and treasury and general manager. His wife, Mr. Margaret Worthington and Miss Elizabeth Sproule, were the other officers. This time the liabilities were about $132,000 and the assets about $70,000.

Just before his failure Worthington sent a lot of books, worth $8,000 to $10,000, to Chicago, pretending that they had been sold to his wife. The receiver regained possession of them, however.

Worthington apparently spent a great deal of the money he received from the corporation on life-insurance policies. He also bought some property in Sea Cliff, L. I., which he transferred to some one else. There are numerous entries of $35 and $50 in his books of money given to a church for pew rent and as ordinary contributions.

For many years Worthington has been the object of Anthony Comstock’s close attention. At the time of the failure the concern had on hand a number of copies of “Tom Jones” and other book which Comstock said were indecent. Recently Judge O’Brien, of the Supreme Court, decided that the books ere proper and that the receiver could sell them.

Worthington said that instead of having misappropriated the funds of the company, it really owed him a large amount.

[American Newsman 1894-07 p13]. PUBLISHER WORTHINGTON IN JAIL. Richard Worthington, who was general manager of the Worthington Publishing Company of 747 Broadway, which went into the hands of a receiver about ix month ago, was arrested recently by Deputy Sheriff Heimberger on an order signed by Justice Barrett. Joseph J. Little, the receiver of the company, is suing Worthington to recover $19,085.71 alleged to have been fraudulently appropriated to his own use. According to Worthington’s private accounts, not a little of this money went for “pew rent” and “church.”

Mrs. Worthington and Miss Elizabeth Sproule, who were also stockholders in the company, are now in the Catskills. It is alleged that they also obtained from the company, through Worthington, more money than they were entitled to, and a suit has been begun against them also. Mr. Little alleges that altogether, Worthington and his wife and Miss Sproule obtained $60,000 more from the company than was due them.

Richard Worthington is about 60 years old, and since 1870 has had a troubled career as a publisher. He failed and paid five cents on the dollar. In 1885 the Worthington Company was incorporated with a capital of $20,000. The principal stockholders were Richard Worthington, his wife Margaret, and Miss Sproule. Mr. Worthington has variously stated that Miss Sproule was his cousin, was his sister-in-law, and was a friend of his wife, all of which things might be true at the same time. The company came to grief and in October, 1893, it was dissolved and Mr. Little was appointed receiver. The liabilities were $132,000 and assets less than $70,000. This included about $8,000 worth of book that Worthington had shipped to Chicago and said that he had sold to his wife. W. H. Willis as referee decided that these books should go into the assets of the company. He also denied a claim of $60,000 put in by Mrs. Worthington and Miss Sproule.

Mr. Little is the complainant in this case, and he says that during the existence of the company Worthington, as general manager and treasurer, was entitled to a gross salary of $14,541. He began at less than $3,000 a year, and then he and his wife and Miss Sproule voted to increase his salary until he was drawing $3,500 a year. During these years, it is alleged, he appropriated from the company's money $19,085.71 James C. Arnold who was for Worthington’s bookkeeper says that Worthington signed all the commercial paper of the com¬pany and directed the payment of all checks. As soon as the company was organized he began to use company funds to pay his individual debts. Worthington's accounts show a $25 or $50 payment every month or two to the church, the payments made to his tailor, and for the rent or his flat and all individual expenses, including large payments to four life insurance companies. It is alleged that Worthington made no accounting to the company of this money. Miss Sproule and Mrs. Worthington seem to have taken turns acting as president of the company, and as such drawing $1,000 a year salary.

When Worthington was arrested he was taken to the Sheriff’s office, where he remained waiting for a bondsman. His bail was fixed at $5,000 and, as he didn't get it, he was sent to Ludlow street jail.

Mr. James M. Fisk, the receiver's attorney, said yester¬day: We think that Wortthington has money that rightfully belongs to his creditors. We are suing Mrs. Worthington and Miss Sproule to recover about $40,000, which they have obtained from the company without warrant.

After consultation with some of my brethren, we have concluded that the following views should be expressed concerning the merits of this motion: that these books constitute valuable assets of this receivership cannot be doubted, and the question before the court for decision on this motion is whether or not they are of such a character that they should be condemned and their sale prohibited. The books in question are Payne's edition of ‘The Arabian Nights,' Fielding's novel 'Tom Jones;' the works of Rabelais, Ovid's ‘Art of Love,' the ‘Decameron' of Boccaccio, the ‘Heptameron' of Queen Margaret of Navarre, the ‘Confessions’ of J. J. Rousseau, ‘Tales from the Arabic,' and 'Aladdin.'

Most of the volumes that have been submitted to the inspection of the court are of choice editions, both as to the letter-press and the bindings, and are such, both as to their commercial value and subject-matter, as to prevent their being generally sold or purchased, except by those who would desire them for literary merit or for their worth as specimens of fine bookmaking. It is very difficult to see upon what theory these world-renowned classics can be regarded as specimen of that pornographic literature which it is the office of the Society for the Suppression of Vice to suppress: or that they can come under any stronger condemnation than that high standard literature which consists of the works of Shakespeare, of Chaucer, of Laurence Sterne, and of other great English writers, without making references to many parts of the Old Testament scriptures, which are to be found in almost every household in the land. The very artistic character, the high qualities or style, the absence of those glaring and crude pictures, scenes, and descriptions which affect the common and vulgar mind, make a place for books of the character in question entirely apart from such gross and obscene writings as it is the duty of the public authorities to suppress. It would be quite as unjustifiable to condemn the writings of Shakespeare and Chaucer and Laurence Sterne, the early English novelist, the playwrights of the Restoration and the dramatic literature which has so much enriched the English language as been to place an Interdict upon these volumes which have received the admiration of literary men for so many years. What has become standard literature of the English language -- has been wrought into the very structure of our splendid English literature -- is not to be pronounced at this late day unfit for publication or circulation, and stamped with judicial disapprobation as hurtful to the community. The works under consideration are the product of the greatest literary genius.

"Payne's 'Arabian Nights' is a wonderful exhibition of Oriental scholarship, and the other volumes, have so long held a supreme rank in literature that it would be absurd to call them now foul and unclean. A seeker after the sensual and degrading parts of a narrative may find in all these works, as in those of other great authors, something to satisfy his pruriency. But to condemn a standard literary work because of a few of its episodes would compel the exclusion from circulation of a very large proportion of the works of fiction of the most famous writers of the English language. There is no such evil to be feared from the sale of these rare and costly books as the imagination of many even well-disposed people might apprehend. They rank with the higher literature, and would not be bought nor appreciated by the class of people from whom unclean publications ought to be withheld. They are not corrupting in their influence upon the young, for they are not likely to reach them. I am satisfied that it would be a wanton destruction of property to prohibit the sale by the receiver of these works, for if their sale ought to be prohibited, the book should be burned, but I find no reason in law, morals, or expediency why they should not be sold for the benefit of the creditors of the receivershlp. The receiver is therefore allowed to sell these volumes."

In the afternoon of the 28th inst. Mr. Worthington was arrested in front of the Post building on Broadway, New York, on an order signed by Justice Barrett. Mr. Little is suing Worthington to recover $19,085.71, alleged to have been fraudulently appropriated to his own use. According to Worthington's private accounts, not a little of this money went for "pew rent" and "church."

Mrs. Worthington and Miss Elizabeth Sproule, who were also stockholders in the company, are now in the Catskills. It is alleged that they also obtained from the company, through Worthington, more money than they were entitled to, and a suit has been begun against them also. Mr. Little alleges that altogether Worthington and his wife and Miss Sproule obtained $60,000 more from the company than was due them.

Mr. Little claims that during the existence of the company Worthington, as general manager and treasurer, was entitled to a gross salary of $14,541. He began at less than $3000 a year, and then he and his wife and Miss Sproule voted to increase his salary until he was drawing $3500 a year. During these years, it is alleged, he appropriated from the company's money $19,085.71. James C. Arnold, who was for many years Worthington's book-keeper, says that Worthington signed all the commercial paper of the company and directed the payment of all checks. As soon as the company was organized be began to use company funds to pay his individual debts. Worthington's accounts show a $25 or $50 payment every month or two to the church, the payments made to his tailor, and for the rent of his flat and all individual expenses, including large payments to four life insurance companies. It is alleged that Worthington made no accounting to the company for this money. Miss Sproule and Mrs. Worthington seem to have taken turns acting as president of the company, and as such drawing $1000 a year salary.

When Worthington was arrested he was taken to the Sheriff’s office, where he remained until 4 o'clock waiting for a bondsman. His bail was fixed at $5000, and, as he dldn't get it, he was sent to Ludlow Street Jail.

Mr. James M. Fisk, the receiver’s attorney, says: "We think that Worthington has money that rightfully belongs to his creditors. We are suing Mrs. Worthington and Miss Sproule to recover about $40,000, which they have obtained from the company without warrant. Worthington says that his arrest is an outrage, and that when he can get hold of the books be can prove that the company still owes him money.

One of the largest houses on Broadway, not long since, imported a number of "Studies from the Nude,” which have been sold extensively in England and France and which were brought over at very heavy expense, packed in zinc cases, and insured at a high valuation. Announcement was made that the books were for sale, and when Comstock heard of it he walked into the publisher's office and told him that if he put them on sale he would be arrested and "sent up." Then Mr. Comstock walked pompously out of the place. The publisher hesitated two weeks, and then, at a very heavy loss, shipped the entire consignment back to England. There was nothing about the book in any way as indecent or suggestive as the ordinary run of police papers in New York, or the innumerable "living pictures" which are nightly exhibited at the music halls and theatres.

"Aladdin and the Enchanted Lamp." "Zein Ul Asnam and the King of the Jinn." Two stories done into English from the recently discovered Arabic text by John Payne, of the Villon Society. (The concluding volume to and uniform with Payne's "Arabian Nights.") 2 vol., 8vo, 280 pp. $62.50. Clark.

“Tales from the Arabic." Tales not occurring in any other edition of the literal translation of the "Arabian Nights." Done into English by John Payne. 3 vols., 8vo., 914 pp, $79 per volume. Clark:

Fielding (Henry). "The History of Tom Jones, a foundling.' 12mo, 499 pp. $110. F. M. Lupton Pub. Co., 13 Walker sr., N. Y.

He Expired Suddenly Last Night at the Sea Cliff House. Apoplexy Said to Have Killed Ex-Publisher.

THE end has finally been reached, from present appearances, in the involved litigation over the affairs of the R. Worthington Company.