ASIDE [for 1888]

Fussiness was a characteristic of the Eighties. Indeed, "Elaborate" is a more exact alliterative for the decade than "Elegant," for never was there a period when the lily was painted or refined gold gilded more frequently.

The parlor (for the word "living-room" did not come into use until after the turn of the century) was a-flutter with draperies. The windows were hung with heavy lambrequins[*] (if one could afford them); and draperies, hanging from a gilt cornice, were heavily braided. Hand-made lace edged the heavy net under-curtains, if one had plenty of money. But, even if one had little of this world's goods everything must be draped. Chairs had ribbons or silk sashes tied on them. Mantels were draped with lambrequins of felt or plush, embroidered in chenille. Goldenrod and daisies formed a good design. On each picture-frame hung a silk "drape;" which added to the artistic atmosphere of the apartment.

In calling attention to a wood-cut of a boudoir in a New York suburban residence, the editor of Hill's Album of Biography and Art says:

"This is a beautiful room, made so because taste and wealth have evidently been combined in its adornment. Examination will show, however, that artistic knowledge in arrangement is the cause of its chief beauty. Thus, in any house, while more or less of money may be necessary to decoration, the interior may be made beautiful out of scraps and articles that would otherwise go to waste."

In this connection suggestions are made for using odds and ends. A waste-basket may easily be made from wires obtained at a hardware store. Or, as an alternative, a few pieces of wood may be used, sixteen or eighteen inches high and fastened together by barrel-hoops. This foundation may be trimmed with cords and tassels. A round cheese-box is recommended for the foundation for a comfortable footstool, of which there should be one or two in each room, says the editor.

Another suggestion is the purchase of a number of boxes at a shoestore. "Five, six or eight of these will make, when nailed together, a convenient cupboard. This can be papered with scraps of wall-paper and border," says the editor, "and with a curtain of common calico will be an ornament to the room."

Many women with skillful fingers did make little tables of spools which they accumulated by saving or begging them from friends. These small tables were stained or painted white, and with a red ribbon tied on one leg, such a piece of furniture was thought a handsome addition to the room. Not too steady on its legs, was this spool-table, but at least you had made something out of nothing.

On the parlor center-table, which had to be substantial, was a wool cover, usually of dark-red or green, with a plush border. Sometimes this border was ornamented with a Greek design in gold thread.

A lamp stood on the center-table, for, even if the room was lighted by gas, it needed a lower light, for reading. Beside the lamp was the plush photograph album, with cabinet photographs of all the family. In some of these there were places for the old carte-de-visite size, and a few of these might be found. Sometimes a picture of Tom Thumb, or Queen Victoria or President Garfield might linger among the family likenesses.

In addition to the photograph album there were always gift-books.

Gift-books came in with the Eighties, and were, as the name implies, made to be given away. No one on earth would ever have thought of buying one to keep. It might be said of them, in Scriptural language, "It is more blessed to give than to receive."

Yet they were well-made, bound in mustard-color or olive-green cloth, the titles stamped in gold, with much gold ornamentation.

Tennyson's "Maud"; Longfellow's "Evangeline" or "The Courtship of Miles Standish"; Owen Meredith's "Lucille" . . . these were the ones most often found on center-tables. From "Lucille; one quoted the only lines that seemed at all interesting ... the ones beginning:

"We may live without poetry, music or art"

and ending with

"But civilized man cannot live without cooks".

That was the one virtue of gift-books ... they started conversation, for the caller usually remembered some line in one of the poems and the hostess said: "Yes, it is beautiful. Isn't it?"

Furniture was Eastlake in design, if one had the money for the newest thing. You had probably read Mr. Eastlake's book, Hints On Household Taste, the Bible of young couples going to housekeeping about this time.

Charles Locke Eastlake, R.I.B.A., founder of the Eastlake style ... now so dead that few persons born after 1900 have so much as heard the name ... had some good ideas. He wished to bring back the honest workmanship of the earlier British craftsman. He liked the Gothic and his designs were high and pointed. But when his book came to America and American manufacturers began to copy his designs, they did it in machine work. Modifications of his ideas made American furniture of the Eighties quite terrible, and if Charles Locke Eastlake had seen the crimes committed in his name, he must have wished he had never put pencil to paper.

Yes, it was an ugly period, so far as decoration was concerned. Yet, remembering the dining-table cleared, with a hanging-lamp burning brightly above; a plate of red apples and a dish of pop corn handy; one of the family reading Mark Twain or Edward Eggleston or the children's magazines, Saint Nicholas or Youth's Companion, while the others sewed, it seems a time to look back on with tenderness.

..................

[*] Lambrequin = a piece of ornamental drapery or short decorative hanging, pendent from a shelf or from the casing above a window, hiding the curtain fixtures, or the like.

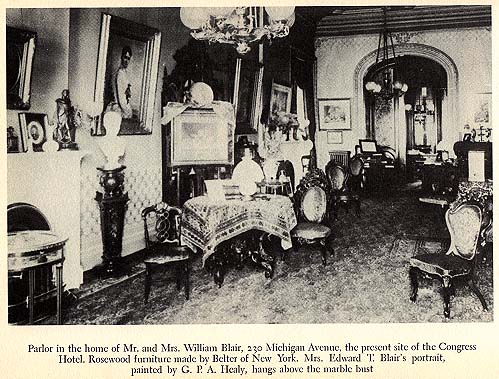

Pages 221-223 from Herma Clark, The Elegant Eighties: When Chicago Was Young, with a foreward by John T. McCutcheon. Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co., 1941. Clark served as secretary to a prominent Chicago businessman, William Blair, and continued as the secretary of his widow, Sarah Seymour Blair, until her death in 1923. After Mrs. Blair's death, Clark thought to try "record Chicago's social life of yesteryear, as I had learned it from the lips of Mrs. Blair and her friends. I decided to put the story in the form of letters from a fictitious writer ... who should have some of the experienes that Mrs. Blair had had and should meet some of the people she had met." These "letters" were published as a series in the Chicago Tribune during the 1920s and then gathered in The Elegant Eighties in 1941. Clark placed endnotes and an "Aside" at the end of the group of letters for each year.

Last revised: 12 August 2010