The following 1873 account of American bookmaking reflected industrial practice in 1860, when Lucile was first published, and that practice had not changed much by the time Lucile began to fade in popularity after 1910. For a separate account of stereoplating and electroplating -- nearly all editions of Lucile were produced from plates made in one of these ways -- see the article on Stereoplating from this same source.

BOOK-MAKING.

BOOK-MAKING.

ANCIENT BINDING OF MANUSCRIPTS. - THE SUPPOSED INVENTOR. - BINDING IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY. - SPLENDOR OF THE SPECIMENS. - PROGRESS OF THE ART. - MATERIALS USED. - GOLD, SILVER, AND PRECIOUS STONES. - BRITISH BINDINGS. - ARTISTS ON THE CONTINENT. - CHEVALlER JEAN GROLIER. - D'EON. - PADELOUP. - CELEBRATED LONDON BINDERS. - ROGER PAYNE AND OTHERS. - FAMOUS MODERN ARTISANS IN LONDON AND PARIS . - BOOK MAKING IN AMERICA . - THE FIRST BOOK IN BOSTON . - THE EARLIEST BINDER. - PROGRESS OF THE INDUSTRY IN BOSTON , NEW YORK , AND PHILADELPHIA . - BENJAMIN FRANKLIN'S BINDERY. - THE ART. - DETAILS OF THE PROCESSES. - USE OF MACHINERY. - AMERICAN INVENTIONS. - MANUFACTURE OF CASES. - PROCESS OF PUTTING ON. - OTHER KINDS OF WORK. - IARBLING, SPRINKLING, AND GILDING. - EMBOSSING. - BOOK PUBLISHING. - GROWTH OF THE BUSINESS IN THE UNITED STATES. - EXTRAORDINARY SALES OF CERTAIN WORKS. -WEBSTER'S SPELLING BOOK. - "UNCLE TOM'S CABIN." - "SUNSHINE AND SHADOW." - BIBLE DICTIONARY. - BOOKS SOLD ONLY BY SUBSCRIPTION. - USEFULNESS AND POPULARITY OF THIS KIND OF PUBLISHING.

Another article in this volume (see PRINTING AND THE PRINTING PRESS) gives the history of the discovery of printing, its progress, its introduction into America, and describes in detail the various processes of composition, press work, etc., or, in other words, the preparation of the printed sheets for the binder, who makes them into books. Of course bookbinding was coexistent with book printing, or rather it is of far greater antiquity, since manuscripts from time immemorial were protected by wood, metal, or leather covers, and the even older books of wood or metal plates were fastened at the backs by thongs or hinges, which furnished a rude binding.

Phillatius, an Athenian, is credited with the invention of sewing sheets of vellum and papyrus together, and securing the backs with glue. Boards or covers would naturally be the next step, and literal boards of wood were first used, which after a while were covered with parchment or leather. The Romans brought the art to great perfection, especially in the ornamentation of the wooden covers by carvings. In the thirteenth century the monks bound their illuminated manuscripts with covers, which were frequently enamelled, ornamented with gold and silver, enriched with precious stones, and covered with figures beautifully carved in wood. Some of these early bindings exhibit boards an inch or more in thickness, in which were covered recesses for relics and crucifixes. A century later ivory tablets, colored velvets, morocco, vellum stamped with gold, tooling, inlaid calf and morocco covers, and gold and silver clasps and corners, were employed in binding and ornamenting the Gospels and Missals. Many magnificent specimens of the fourteenth and two following centuries -- bindings that have never been surpassed in richness and elaboration -- are preserved in the great public and private libraries of Europe . A field or farm would scarcely purchase one of these volumes when fresh from the binder, and their value, as relics of by-gone centuries is even greater now.

The invention of printing made general the use of calf and morocco bindings on oaken boards, and stamped in gold or in" blind tooling." The British Museum has many books bound in England in the time of Henry VII. The period of Henry VIII. produced many magnificent specimens of binding, and under Elizabeth embroidery bindings were introduced. Folios of that period in plain calf show most substantial work.

On the continent bookbinding fairly took rank as a fine art, and early enlisted the attention of true artists. Chevalier Jean Grolier was famous for the elaborate patterns which he drew for his own book-covers; Chevalier D'Eon introduced the Etruscan designs as ornaments; Padeloup tooled books so that they looked as if they were bound in gold lace; and Derome and De Seuil -- the latter immortalized in one of Pope's poems -- were famous bookbinders. The Cambridge binding of the eighteenth century is justly celebrated. Roger Payne, who began business in London in 1770, may be said to have opened a new era in the art.

Payne was a man of most dissolute habits; but as a thorough artist, especially in finishing, he was far in advance of all who preceded him, and in his own day he had no rival. His success lay in his style, which was original, in his invention and manufacture of elaborate embellishing tools, and in his choice and working of materials and ornaments. Superb specimens of his work are preserved in English' libraries, particularly in Earl Spencer's, and bibliographers speak of him in the highest terms of praise. After Payne, Kalthoeber, Staggemier, Falkner, Hering, and Walther deserve especial mention. Mackenzie, Lewis, Clarke (celebrated for his tree-marbled calf), Bedford, and Hayday are among the more famous of modern London binders. All book-buyers know how much the name of a binder sometimes enhances the value of a volume. Trautz, Niédre, Capé, Lortic, and Duru are among the most noted of modern French binders, and their work, for its ornamentation and perfection of detail, is highly prized.

BOOK-MAKING IN AMERICA .

The first bookbinding done in the colonies was by John Ratliffe, an Englishman, who came over expressly to bind Eliot's Indian Bible, printed at Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1661-63, and Ratliffe could bind only a single copy in a day. The first book printed in Boston was in 1676. The early provincial governors were instructed to prohibit printing, which was looked upon as the means of disseminating disobedience, heresies, sects, and libels. But book-makers thrived nevertheless. From 1684 to 1690, Pierce, mentioned as the fifth printer in Boston , published several books for himself and for booksellers. Bartholomew Green followed in 1690, and from that time forward the art has progressed, till Boston has become one of the great book-making centres of the Union. In Philadelphia book-printing began in 1686; in New York in 1693, with the publication by Bradford of the Laws of the Province in small folio. In 1726 New York had a second publisher. When Franklin, a boy of seventeen, went to Philadelphia in 1723, Samuel Keimer, who employed him, had just started the second press in that city, and besides him the Bradfords were the only publishers in Philadelphia and New York .

Previous to the issue of Eliot's Indian Bible, copies of the Psalms and of the Laws, bound in parchment, appeared in Boston, a copy of the Psalms as early as 1647; but by whom they were printed and bound, or whether the work was done in England , is uncertain. Up to the time of the Revolution there had been thirty binderies in Boston. New York had a bindery in 1769; Benjamin Franklin's bindery, in Market Street , Philadelphia , was in operation in 1729; and two Scotch booksellers in Charleston, S. C., had binderies in 1764 and 1771.

After the Revolution the progress of book-making in the United States was rapid. In 1808 was issued Barlow's Columbiad, in quarto, illustrated with plates engraved in London, and by far the finest book published in the country up to that time. Two years later Wilson 's American Ornithology, in seven volumes folio, with colored plates, was issued in Philadelphia. In 1822 an American reprint of Rees's Cyclopedia was published in Philadelphia, in forty-one volumes, with six additional volumes of plates, and was the greatest venture of the kind which had been undertaken in the country. In 1830 books to the value of three million five hundred thousand dollars, one-third of them school books, were printed in the United States. Since that time, with the increase of population, the general diffusion of education, and the introduction of machinery and other facilities, the growth of the book business in the United States has been enormous.

PROCESSES IN BOOKBINDING.

PROCESSES IN BOOKBINDING.

The printed sheets go from the press to the drying-room, where they are hung on frames in a steam-heated temperature of from one hundred to one hundred and twenty degrees, and remain from half all hour to an hour. They are then placed between pressboards, with a highly-glazed surface; if very nice work, a single sheet between two boards, and sometimes a “set-off " sheet of paper on each side of the printed sheet, but ordinarily three or four sheets between every pair of press-boards. A pile of these boards, with the interleaving sheets, is then subjected to hydraulic pressure equal to six hundred tons for a half day, or in some cases longer. From the hydraulic press the sheets go to the cutting machine, which rapidly cuts them in two. Then most ingenious machines, of different capacity, fold the sheets into pages of the required size and form for a book, making them ready for sewing The folding gives the name describing the size of a book; thus a sheet once folded into two leaves, or four pages, is a folio; folded again, it is a quarto; folded once more, as in the case of this volume, every sheet gives eight leaves, or sixteen pages, and the book is called an octavo; folding into twelve leaves, or twenty-four pages, makes a duodecimo, and so on for smaller volumes. This folding was formerly done by hand; now one girl tends a machine which will do the work of several girls with great rapidity and accuracy.

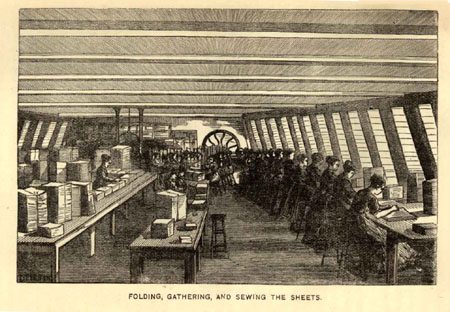

The folded sheets are then tied in bundles, till the entire sheets of a single work are folded, when they are placed in order in piles, and a girl going from pile to pile rapidly gathers and collects the pages for a volume, and volume after volume, till the sheets are exhausted. These go to the smashing machine, which has superseded the old method of hammering by hand, and the more recent of screw-pressing, and instantly presses the pages solidly together. The sawing machine then saws the backs simultaneously, with the four, five, or six grooves necessary to receive the cords through which the thread is passed in sewing the different sheets so as to unite them all together. The books are now carried to sewing frames, where they are sewed by girls, who perform their work with singular dexterity, deftly passing the needle through each "form," and securing it to the cords at the back. Machines have been invented for book-sewing, but they have not been generally introduced, and the labor is usually, even in the most extensive establishments, performed by girls.

After sewing, the books are "drawn off," cut apart, and taken the trimming machine, which has superseded the old "ploughing” by hand process, and which, with great rapidity, trims the three sides smoothly and accurately. The next process is rounding the backs, which is done with the hammer. A thin coat of glue, previously applied, holds the round in shape; then the backing, which forms the joint where the cover opens, in small books, done by a machine, but on most of the larger books by hand, with a press and hammer. The back is now covered with a piece of muslin nearly the whole length, and extending an inch over the sides, to strengthen the joints; and over the muslin is pasted a piece of paper. The head-bands, consisting of a doubled piece of muslin, and sometimes of knit silk, are put on, and the book is sprinkled, marbled, or gilded on the edges, though in the cheaper and smaller-sized books the edges are left plain.

In sprinkling, several books are taken together in a row, on boards, and the color or colors selected are sprinkled with a large brush, or are rubbed through a sieve with a stiff brush, producing the fine dust-like coloring seen on the edges of books. In marbling, the artist -- for a skillful artisan in this department is an artist -- sprinkles his colors upon a preparation of mucilaginous liquid in a wooden trough, and then with "combs" makes the “comb-work," which is the pattern most usual for the edges. With various colors, and by skilful sprinkling, he makes the different patterns known as shell, -- of various colors and differently veined, blue stormont, light Italian, west end, curl, Spanish of all colors, antique, wave, British, Dutch, and so on, in great variety, for marbling paper used for the sides of books. If the book is to be gilded, the edges are scraped, a ground work of red chalk is laid on, albumen, or the white of an egg, with water, forms the size on which the gold is laid, and is subsequently burnished with blood-stone and agate. Over this is sometimes laid gold of another color, which is stamped in patterns in the edges, and the superfluous gold of the upper coat is brushed off, leaving the figures.

In cloth-bound books the cloth is cut the proper size, and glued to the boards (in the early stages of book making they were made of wood -- but at the present time tarred rope is used, or other stock such as is used in making cheap, coarse paper) which form the stiffening for the sides, and when thus made are called cases . Ornamenting the sides and back of the case is then done by having engraved, in brass, the design required. That is fastened to an embossing press, where it is kept heated with steam, and by strong pressure leaves its imprint on the cover. When the impression is wanted in gilt, the case is prepared, and gold leaf laid on where the stamp is to come. The books are then glued or pasted into the cases, and pressed in brass-bound boards to form the groove where the joint is. After the final pressing, the book is ready for the reader.

Binding in leather and morocco, or half binding with calf or morocco backs and corners, and paper or cloth sides, requires more hand work. The books are generally laced into the covers; the lettering and the various designs, in gold and blind tooling, are done by hand; and to this binding the only limits are the cost of the work and the ingenuity of the binder. Machinery is much more employed in the United States than in Europe, and most of the ingenious and labor-saving machinery used in bookbinding is of American invention.

The foregoing is designed to give, in the briefest possible manner, an intelligible idea of the ordinary processes of book-making, as seen in the extensive and first-class establishment of Messrs. Case, Lockwood & Brainard, at Hartford, Connecticut .

BOOK PUBLISHING.

BOOK PUBLISHING.

In a work of this kind it would be useless to give statistics of the extent of the book-publishing business in the United States, since it is so rapidly increasing that the figures for one year would give no idea of the business of the year following. It is among the most progressive, profitable, and important industries of the country. Mention may be made of single works sold in the United States . Of Webster's well-known Spelling Book more than fifty-five million copies have been printed, the sales now reaching a million and one quarter-copies a year, and of the different editions of Webster's Dictionary three hundred thousand copies are sold annually. Of "Uncle Tom's Cabin" more than half a million copies have been sold in the United States; various editions of the same work have been sold in England to the extent of a million and a half of copies; it has been translated into every European language, and even into Armenian and Arabic.

Within a few years an important branch of the business has grown up in the publication of books for sale solely by subscription. By this mode of publication thousands of valuable books have reached buyers who otherwise would not have purchased, and by this dissemination of works of an entertaining and instructive character, intelligence has been diffused, and the country has been benefited. Some of these subscription books have reached extraordinary circulation. Of "Sunshine and Shadow," published by Messrs. J. B. Burr & Hyde, one hundred and fifty thousand copies have been sold; of the Bible Dictionary, seventy-five thousand copies; of other works published by the same house from thirty thousand to one hundred thousand copies of each, and with a steady demand for all. This kind of book publishing is becoming more and more popular throughout the country every year. It is found to be the best, indeed almost only, means of introducing to a large circle of readers, especially in interior towns which are remote from book-publishing and book-selling centres, standard works of a high character, and this means of diffusion, by its enormous extent, enables the publishers and their agents to sell interesting and entertaining works, profusely illustrated, at far less prices than works of the same character can be afforded by the usual method of book publishing.

From The Great Industries of the United States: Being an Historical Summary of the Origin, Growth, and Perfection of the Chief Industrial Arts of This Country. By Horace Greeley, Leon Case, Edward Howland, John B. Gough, Philip Ripley, F. B. Perkins, J. B. Lyman, Albert Brisbane, Rev. E. E. Hall, and Other Eminent Writers Upon Political and Social Economy, Mechanics, Manufactures, Etc., Etc. With over 500 illustrations. Hartford : J.B. Burr & Hyde; Chicago and Cincinnati: J. B. Burr, Hyde & Co. 1873. p181-191.

Last revised: 8 December 2010